6 minutes

UTCTF recur challenge

Over the weekend, I participated in the UTCTF 2021 but was unable to spend a lot of time on the challenges. One of the challenge I worked on was the recur challenge in the Reverse Engineering category. The challenge was not that hard but I had fun working on it so I decided to write a writeup for the challenge.

The challenge had a binary file attached with it and the description of the challenge was

I found this binary that is supposed to print flags. It doesn’t seem to work properly though…

I usually run the file command on the challenge binaries just to know if they are stripped or not. A stripped binary has no debugging symbols which makes it harder to debug and reverse. Here is an article that compare the two and explains how to deal with a stripped binary.

Back to the challenge, here is the output of the file command on our binary -

$ file ./recur

recur: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=ffe1273695471373b182d4f5f266181d893ba3d8, for GNU/Linux 4.4.0, not stripped

Not stripped which means it would be easy to debug. I also execute the binary just to get an idea of the output. Like the description said, the binary prints the flag but is stuck after {

$ ./recur

utflag{

For the reversing challenges, I use Ghidra which is a well known reverse engineering tool and is used for generating C source code from an executable. The decompiled binary had the main function and a function called recurrence. Here are the source codes of the two functions

int main(void) {

byte bVar1;

byte bVar2;

int local_1c;

local_1c = 0;

while (local_1c < 0x1c) {

bVar1 = flag[local_1c];

bVar2 = recurrence();

putchar((int)(char)(bVar2 ^ bVar1));

fflush(stdout);

local_1c = local_1c + 1;

}

return 0;

}

ulong recurrence(int param_1) {

int iVar1;

int iVar2;

ulong uVar3;

if (param_1 == 0) {

uVar3 = 3;

}

else {

if (param_1 == 1) {

uVar3 = 5;

}

else {

iVar1 = recurrence((ulong)(param_1 - 1));

iVar2 = recurrence((ulong)(param_1 - 2));

uVar3 = (ulong)(uint)(iVar2 * 3 + iVar1 * 2);

}

}

return uVar3;

}

The code is pretty readable and instead of going through it line by line, here are some things which we learn from the code.

-

The

recurrencefunction defines a recurrence relation that can be described asf(x) = 3 if x = 0 = 5 if x = 1 = 2 * f(x-1) + 3 * f(x-2)This is similar to the Fibonacci sequence.

-

The

mainfunction reads28bytes asflagand a new character is evaluated using theflagbyte and the output of therecurrencemethod. -

The new character is calculated using the

XORoperation.

Since, the output of the recurrence function is used in calculating the output character, we need the input to the recurrence function. The decompiled code does not show what is provided as input to the function. Also, the 28 bytes needed for flag need to be located. For both these problems, I used gdb to go through the assembly of the binary.

Here is the assembly of the first few lines of the main function -

pwndbg> disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x000000000000119c <+0>: push rbp

0x000000000000119d <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x00000000000011a0 <+4>: push rbx

0x00000000000011a1 <+5>: sub rsp,0x18

0x00000000000011a5 <+9>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x14],0x0

0x00000000000011ac <+16>: jmp 0x11ea <main+78>

0x00000000000011ae <+18>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x14]

0x00000000000011b1 <+21>: cdqe

0x00000000000011b3 <+23>: lea rdx,[rip+0x2e86] # 0x4040 <flag>

As you can see, gdb has pointed out that the flag is stored at 0x4040 and all we need to do is read 28 bytes from this address.

pwndbg> x/28bx 0x4040

0x4040 <flag>: 0x76 0x71 0xc5 0xa9 0xe2 0x22 0xd8 0xb5

0x4048 <flag+8>: 0x73 0xf1 0x92 0x28 0xb2 0xbf 0x90 0x5a

0x4050 <flag+16>: 0x76 0x77 0xfc 0xa6 0xb3 0x21 0x90 0xda

0x4058 <flag+24>: 0x6f 0xb5 0xcf 0x38

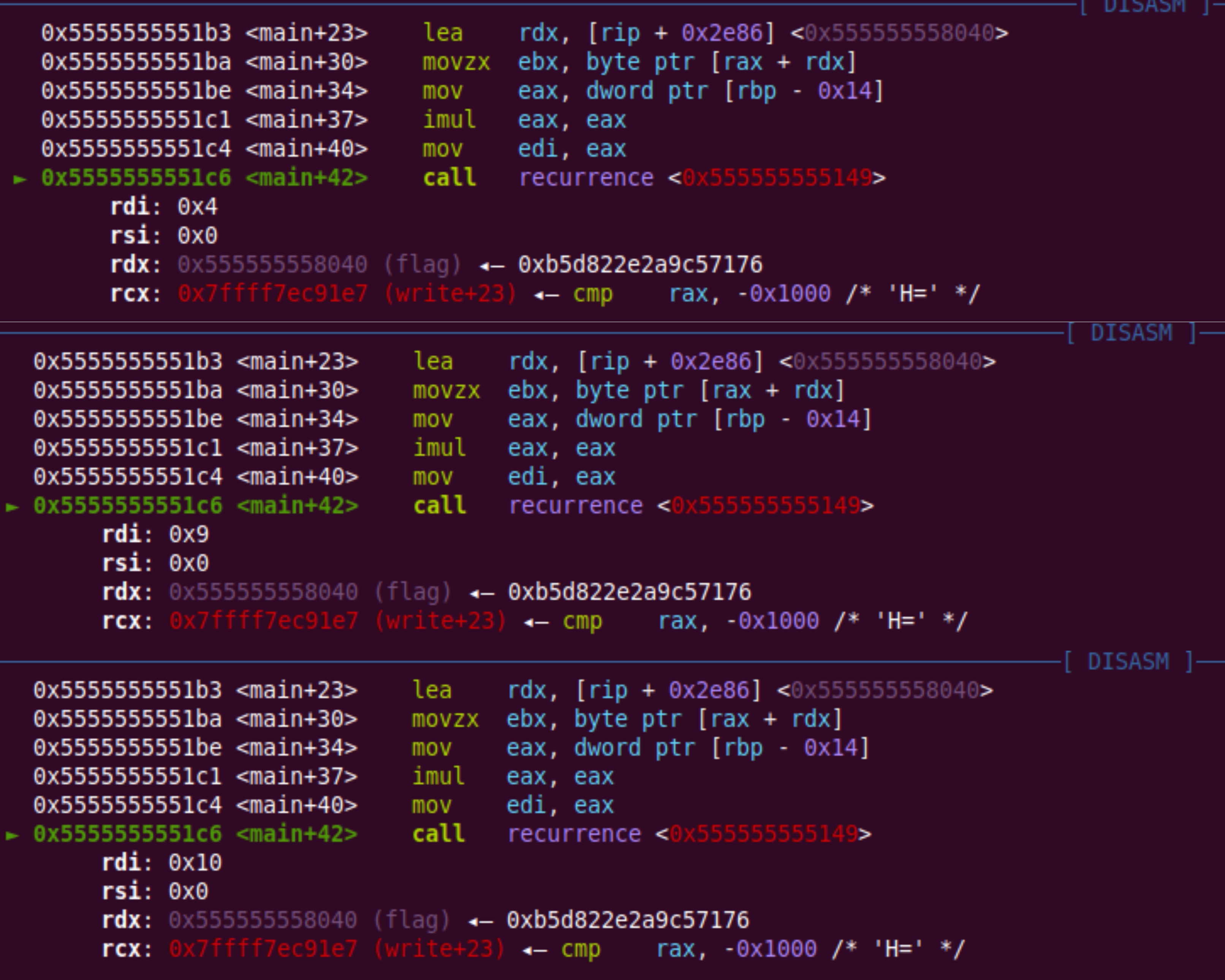

Next, we need to check what argument is provided to the recurrence function. For this, I just executed the binary instruction wise and observed the argument to the method. Here are the disassembly of the recurrence during the 3rd, 4th and 5th iteration.

It is clear that the method takes the square of the iteration number as input. This explains why the flag stops printing after the 7th character since f(64) is heavy to compute.

Here is a python script I wrote that covers everything we have discussed so far.

def recur(n):

if (n == 0):

return 3

elif (n == 1):

return 5

else:

return (2 * (recur(n-1) % 256) + 3 * (recur(n-2) % 256)) % 256

flag = [0x76, 0x71, 0xc5, 0xa9, 0xe2, 0x22, 0xd8, 0xb5, 0x73, 0xf1, 0x92, 0x28, 0xb2, 0xbf, 0x90, 0x5a, 0x76, 0x77, 0xfc, 0xa6, 0xb3, 0x21, 0x90, 0xda, 0x6f, 0xb5, 0xcf, 0x38]

res = []

for i in range(len(flag)):

val = (flag[i] ^ recur(i * i)) % 256

res.append(val)

print(chr(val))

print(''.join(list(map(lambda x: chr(x), res))))

The script is pretty easy to understand and I used mod 256 since we know that the char in C is 1 byte which means that only values 0-255 are present.

If we run this script, we get the same result as the executable ie the binary is stuck after the 6th character. The solution to this involves the concept of Memoization which basically means that we remember already computed states and reuse their output instead of re-executing the function. We could use a dict object that saves n as key and the output as value. Python provides an interesting module - functools which has the lru_cache method that saves up the output of the recent function calls. Here is the final script that works.

import functools

@functools.lru_cache()

def recur(n):

if (n == 0):

return 3

elif (n == 1):

return 5

else:

return (2 * (recur(n-1) % 256) + 3 * (recur(n-2) % 256)) % 256

flag = [0x76, 0x71, 0xc5, 0xa9, 0xe2, 0x22, 0xd8, 0xb5, 0x73, 0xf1, 0x92, 0x28, 0xb2, 0xbf, 0x90, 0x5a, 0x76, 0x77, 0xfc, 0xa6, 0xb3, 0x21, 0x90, 0xda, 0x6f, 0xb5, 0xcf, 0x38]

res = []

for i in range(len(flag)):

val = (flag[i] ^ recur(i * i)) % 256

res.append(val)

print(''.join(list(map(lambda x: chr(x), res))))

And here is the output of the script with the flag -

$ python3 exploit.py

utflag{0pt1m1z3_ur_c0d3_l0l}

Overall, I think it was not that hard of a challenge but it is a good challenge for someone who is starting reverse engineering and wants to familiarise themselves with the tools commonly used. Thanks for reading. Cheers!